Integrating Python into an iOS App

How Diamond Kinetics Plays by the Laws of Physics

One of the unique opportunities Diamond Kinetics provides to our iOS team is the challenge of integrating our app with our Bluetooth device. Whether attached to the end of a bat in one of our high-performance mounts or integrated into a Marucci Smart Bat, the device leverages several sensors to capture how the user performs the swing of the bat and sends that data to the iOS app via a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) connection.

While we plan to have a post in the future that discusses the intricacies and lessons learned about our BLE connection, we will focus this post on what we do with that raw data when it gets to the iOS device. We turn it into meaningful metrics to help our users get better at swinging in their pursuit of improving their game. How we make that happen, and some recent obstacles we faced when trying to keep current with the latest changes in iOS development posed some interesting problems to the team that we’re excited to share.

Background

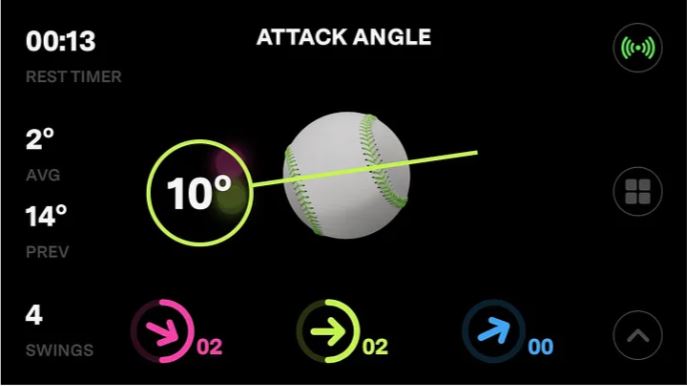

As it is currently implemented, the Diamond Kinetics (DK) smart device is responsible for collecting the data from multiple hardware sensors and pumping that data over a BLE connection to its paired iOS device. Once the iOS device receives that data, it needs to run the raw data through the necessary calculations, leveraging digital signal processing and rigid body dynamics, to determine metrics that are informative to the user. These metrics include numbers such as the barrel speed and trigger-to-impact time for swings taken with the DK bat sensor.

We at DK refer to these calculations collectively as our Physics Engine. While this processing could run in the cloud, we choose to run natively on the device. This allows us to provide the results to the user with as little latency as possible while also enabling users to use the app offline or in a situation where the network performance would limit the experience if the calculations required a round trip to our server in the cloud.

Why Python?

The Diamond Kinetics Physics Engine has existed in many different forms since its inception nearly a decade ago. Previous versions existed in multiple languages, including MATLAB originally, C for a brief period of time, and JavaScript for an even shorter period of time. The team settled on Python because it is the language of choice for mechanical engineers and machine learning experts, allowing for knowledge transfer amongst the subject matter experts tasked with maintaining and improving the Physics Engine. It also allows for portability as Python environments can be found on a multitude of computing platforms.

Mobile platforms, most notably iOS, do not support Python for native application development. This limitation can be overcome, however, because Python can be compiled down to C binaries through Cython, and iOS apps can integrate with C binaries. Thankfully, DK has been able to leverage an open-source third-party library called Kivy that exists to turn Python code into mobile apps. While the nominal use case for Kivy is building full mobile apps in Python, we at DK have been able to leverage it just to turn the Python code we need to run on iOS into an xcframework file that we link against the main app.

How it Works

The Diamond Kinetics Physics Engine exists in its own source code repository where it can be maintained and iterated upon as new improvements come to light. When the DK Sensing team decides to release a change, they apply a tag to the repository, and the build server detects that new tag and kicks off a build. This build pulls down those latest changes and invokes the Kivy iOS toolchain to build a library that the DK iOS team can link against the mobile app. Up until recently, this produced a static library containing the Python code compiled into a binary from which the iOS team could use Xcode to generate a “fat” framework where that same binary would work on both iOS devices and simulators such that the iOS team could develop against it and release it as part of the Diamond Kinetics app on the App Store.

Recent Challenges and How We Addressed It

The Kivy iOS toolchain has existed for quite a while, and Diamond Kinetics was able to use it sufficiently to build our Physics Engine for use both on iOS devices and in the iOS simulator. When Kivy was originally developed, it was built under the assumption that the physical device ran on an arm64 platform, while the simulator ran on an x86_64 platform. That assumption was completely valid until Apple announced they were transitioning the macOS hardware from Intel to their Apple Silicon (M-series) processors starting in 2020. When running macOS on an Apple Silicon machine, the simulator natively runs on the arm64 CPU. Apple did provide a virtualization layer, named Rosetta, to allow applications, including Xcode and the iOS simulator, to run in x86_64 mode on top of the underlying new hardware. Initially, an application developer who wished to build code against the DK Physics Engine on an Apple Silicon machine would have to put all of Xcode in Rosetta mode, but in Xcode 14.3 Apple removed that option. Instead, the build system would detect that the binary needs to run in Rosetta mode on the simulator and start the simulator in Rosetta mode. This simulator setting would influence how SwiftUI Previews were run. As of Xcode 15, however, SwiftUI Previews have stopped using Rosetta. All this is to say we knew our days of being able to rely on Rosetta mode were numbered.

Luckily, the open-source maintainers of Kivy iOS heard our pleas and accepted the task of providing a means for building the toolchain so that we could build our library to support arm64 iOS simulators. Not only that, but with the latest mainline of the Kivy iOS repo, we are now able to build for the arm64 simulator, and it clears the path for future exploration of bringing our Physics Engine to other Apple platforms, including tvOS and watchOS, if we so desire.

What’s Next for DK

Armed with our newly created Physics Engine binaries that work across iOS devices and simulators that run on Apple Silicon (arm64) machines, we expect to be more efficient and productive now that we don’t need to run the simulators in Rosetta mode. This should also allow us to reclaim the ability to use additional iOS development tools, including SwiftUI Previews and the Instruments profiling tools, which had stopped working for us when using a simulator in Rosetta mode. Going forward, for our development and CI machines, now that they are all Apple Silicon machines, we expect to get the best performance without the additional translation layer.

One limitation we have not overcome, at least as of this writing, is cross-compiling the Physics Engine to work on any simulator (x86_64 or arm64) independent of what machine was used to build the library. So far we are only able to create the same architecture as the machine it was built on. Given that all of the development team had already moved to Apple Silicon machines, we used this opportunity to upgrade our build machine, which we use as a GitHub Action self-hosted runner, from an Intel machine to a new M2 Pro Mac mini.

We had originally planned to consider using Xcode Cloud for our CI jobs, as that’s more scalable and reliable to have Apple maintain the infrastructure instead of relying on a single machine hosted on our office Internet connection and power systems. We were surprised to learn that Xcode Cloud appears to be run on legacy Intel (x86_64) machines, so our inability to cross-compile prevented us from using Xcode Cloud for our CI process. We do expect that someday Apple will retire all Intel machines from Xcode Cloud, but we have no way of knowing when. For now, we will continue to use our own build machine. Alternatively, we would consider using GitHub-hosted runners, but the macOS costs are significantly more expensive than other platforms. Since Apple requires developers for their platforms to use macOS, our other alternative would be to use AWS’ hosted Apple Silicon hardware as outlined in this post.

To wrap up, we are excited to finally be able to use our Apple Silicon machines to their fullest extent by retiring our dependency on x86_64 architecture. With these improvements, we expect to be able to stay on the cutting edge of app development and use the right tools for the job to continue moving forward with the development of Diamond Kinetics technology.